Black Workers Really Do Need to Be Twice as Good

African American employees tend to receive more scrutiny from their bosses than their white colleagues, meaning that small mistakes are more likely to be caught, which over time leads to worse performance reviews and lower wages.

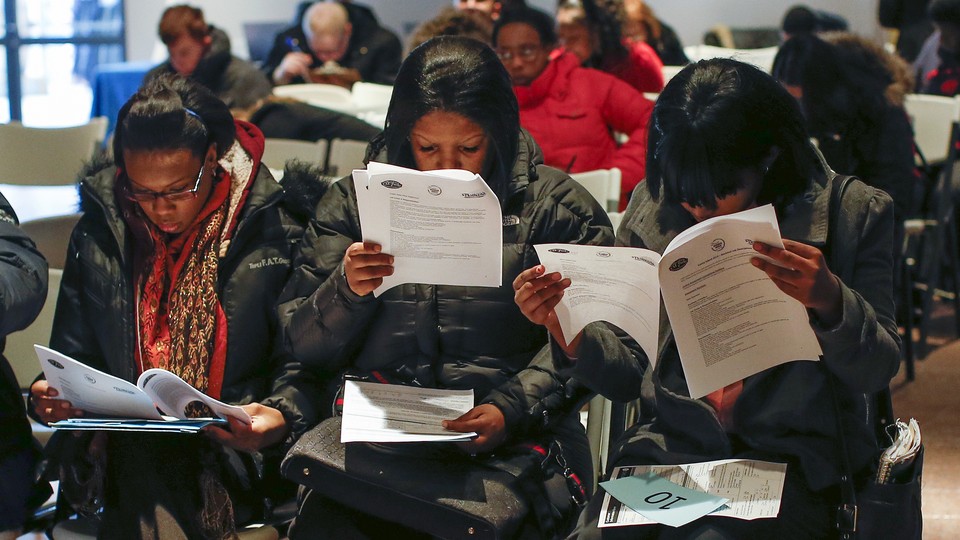

For decades, black parents have told their children that in order to succeed despite racial discrimination, they need to be “twice as good”: twice as smart, twice as dependable, twice as talented. This advice can be found in everything from literature to television shows, to day-to-day conversation. Now, a new paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research shows that when it comes to getting and keeping jobs, that notion might be more than just a platitude.

There’s data that demonstrates the unfortunate reality: Black workers receive extra scrutiny from bosses, which can lead to worse performance reviews, lower wages, and even job loss. The NBER paper, authored by Costas Cavounidis and Kevin Lang, of Boston University, attempts to demonstrate how discrimination factors into company decisions, and creates a feedback loop, resulting in racial gaps in the labor force.

The researchers constructed an economic model based on labor market outcomes for unemployed workers. They build on existing data about job duration, unemployment duration, and lifetime earnings, and then simulate how companies determine whether or not new hires are a good fit.

They observe that the pool of unemployed black workers is likely to be seen as less skilled because of more consistent or prolonged unemployment. That can make companies less likely to hire them, and more skeptical once they do. This leads employers to invest more heavily in monitoring black employees. That could be everything from instructing supervisors to closely watch a new hire, or more directly monitoring job performance—for instance how many boxes a worker correctly packs at a shipping center. Because black workers are more closely scrutinized, it increases the chances that errors—large or small—will be caught. According to the researchers it’s more likely that a black employee would be let go for these errors than a white one. Thus another way of looking at the findings, Lang says, is that blacks simply don’t get a second chance.

Once fired, black workers return to the pool of unemployed—where they will once again have a difficult time finding work, prompting their next employer to be wary as well. In the meantime, white workers are less scrutinized, and as a result, they enjoy a longer tenure on the job, which leads to a stronger work history, more skills, and higher wages.

In order to keep a job, black workers also must meet a higher bar. Only in instances where black workers are monitored and displayed a significantly higher skill level than their white counterparts would they stand a significant chance of keeping their jobs for a while, the researchers found. But even in instances where the productivity of black workers far exceeded their white counterparts, there was still evidence that discrimination persisted, which could lead to lower wages or slower promotions.

This all may help explain the continuing gaps in labor market outcomes between black and white Americans. Historically, the unemployment rate of black Americans hovers about 2 percentage points higher than their white counterparts. Right now, the gap is much wider. At the close of the third quarter the unemployment rate for white Americans was 4.5 percent, below the national average of just over 5 percent. For blacks, however, unemployment was 9.4 percent. And that’s an improvement. Unemployment among black Americans only dipped below 10 percent at the start of 2015—more than five years into the economic recovery. The unemployment rate for whites never even topped 10 percent.

Unsurprisingly, all of these job switches mean that black workers can expect to make less over a lifetime than their white counterparts, which can exacerbate the income and wealth gaps between the races. “With a monitoring regime to look forward to at any future job, a black worker revealed to be in a good match could receive less than an unrevealed white worker,” the economists write.

The current system, in which black workers are disproportionately monitored and let go, while white workers are allowed longer stints, isn’t just bad for black people—it’s bad for the labor market overall. Such an arrangement is inefficient since a large pool of the unemployed drags on overall productivity and labor health, and since such bias doesn’t guarantee that the most productive person gets, and keeps, a job.